When James Fawcett ’88 came to UNC as a British Morehead Scholar, he double-majored in history and political science. But his focus was studying America, picking up on the culture and breaking through the barriers of a supposedly common language.

“It helped open my eyes to what America is all about,” Fawcett said.

He rode a motorcycle to and from class every day (except once when it snowed). He developed a love of basketball, burgers and chicken wings. He learned that what he had called a loo is known here as a restroom, and while the British queue up, Americans stand in line. Years later, Fawcett’s experience on this side of the Atlantic helped his family’s two-centuries-old-and-counting malt-making business in Yorkshire benefit from America’s craft beer boom.

“It was a huge benefit, those four years in Chapel Hill,” Fawcett said. “I speak in North American. You automatically break down a barrier.”

Thomas Fawcett & Sons was opened by Fawcett’s great-great-great-great-grandfather in 1809, the year that Thomas Jefferson ended his presidency and Edgar Allen Poe and Abraham Lincoln were born.

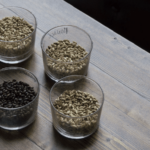

The company is known for producing small-batch malts, which provide the sugary fuel for fermentation to create beer. While wheat, rye, oats, millet, sorghum, rice and even corn have been used for brewing, barley is preferred. To create malted barley, the grain is soaked, allowed to germinate and then heated to stop germination. Malts add both color and flavor to beer.

Thomas Fawcett & Sons is one of only two maltsters in Yorkshire, and it’s one of only a handful left in England that do traditional floor malting. That method, which predates the Industrial Revolution, spreads the grain in about a 5-inch layer on the stone floor of a malt house to germinate. The grain is turned by hand twice a day, seven days a week.

A return, and a return on investment

When he was growing up, Fawcett wasn’t encouraged to go into the family business. In the early 1980s, the brewing industry was struggling. Fawcett said his father resented having to take over the company at age 23 after Fawcett’s grandfather died unexpectedly. “He ran it for 49 years,” Fawcett said of his father. “I think he would have preferred to be a politician.”

Legendary Malts

After college, Fawcett went to work for a London bank. After five years, he grew tired of corporate finance and came around to the family business. Even though his family had been in the trade for centuries, when Fawcett joined the 70-person firm, his father wouldn’t allow him to buy barley for the first seven years, arguing that he had to see seven grain seasons for himself before he could become a competent buyer.

In the late 1990s, Fawcett convinced his father to send him to the Great American Beer Festival in Denver, thinking they could sell to American breweries. Fawcett handed out brochures and talked to many brewers but realized that it wasn’t feasible to ship one ton of malt to a brewery in Montana and another ton to Wisconsin, and so forth. “I got extremely drunk, and then I came home,” Fawcett recalled. When his father asked if he was going to get any return on the $3,000 he spent to send his son to Denver, Fawcett replied: “No.”

But a few weeks later, Bryan Bechard called. The owner of the U.S.-based Country Malt Group had seen one of Fawcett’s brochures in Denver and wanted to distribute the malts in America. Today, Bechard sells about 6,000 tons of Fawcett malt, or about 40 percent of its annual production.

“James very much believes the best quality barley makes the best quality malt,” Bechard said. “It’s obviously worked for them or they wouldn’t still be around.”

Today, brewers across the U.S. use Thomas Fawcett & Sons malts, including several in North Carolina. Some close to home include Pig Pounder Brewery, owned by Marty Kotis ’91, in Greensboro; Fullsteam Brewery in Durham; and Top of the Hill, owned by Scott Maitland ’95 (JD), in Chapel Hill.

Fawcett enjoys having a small role in the burgeoning craft beer scene all over the world. Unlike macrobreweries, microbreweries depend heavily upon the distinctiveness of their ingredients to build their reputations and so have gone searching for products like Fawcett’s. “They can brew the idea that they dreamed up in the bath,” Fawcett said. “They make a better beer, and it gives them an edge over the big guys.”

Unlike his foray into corporate finance, Fawcett said, “I’ve gotten a lot more pleasure producing a product that a lot of people enjoy.”

— Andrea Weigl

Carolina Alumni Review